|

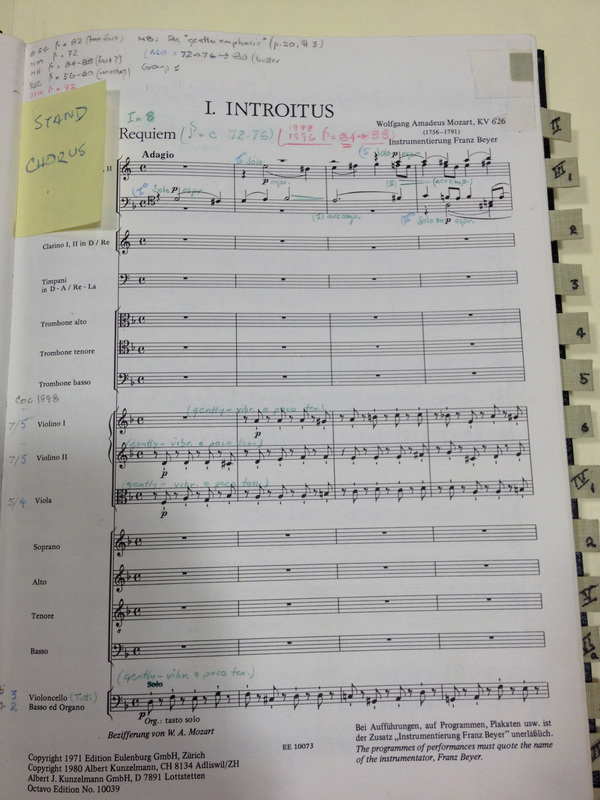

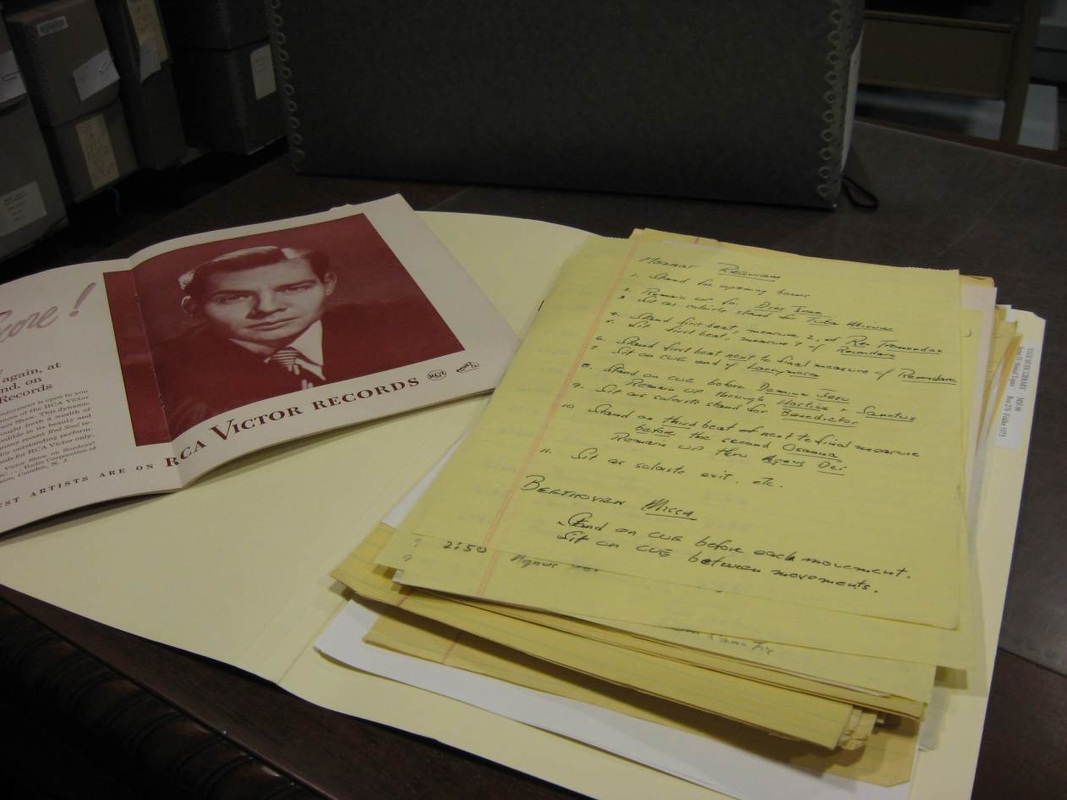

So, what does a conductor do when she’s not actively running from rehearsal to rehearsal? Well, the list is long and includes programming (anywhere from 1 month to 3 years in advance), organizing scores for the upcoming season (I think I’m up to 128 this year, with several programs yet to confirm!), planning rehearsals (how many hours do we need to spend learning Sibelius 1 or Mozart Requiem?), and studying like mad (once the season starts, it’s hard to find enough dedicated time to learn those 128 scores). This week, I had the great fortune of completely “geeking out” at the Yale Library, studying some of Robert Shaw’s papers. I brought my scores of Mozart Requiem, Durufle Requiem, Beethoven 6, and Copland Old American Songs, hoping to glean some information from the great philosopher-conductor. In his papers were his scores and orchestra parts with thousands of markings, multiple stacks of study notes, letters from colleagues, and more. It was marvelously informative, a bit overwhelming, and certainly humbling. Above all, it felt almost like a private lesson with the late Mr. Shaw. Here are a few highlights: I packed up my car to make the drive up north. In addition to the music I brought to Yale, I had to pack my John Williams scores for the Richmond Symphony’s opening concert. (I must admit to studying the Williams while watching the Olympics – quite an appropriate combination, actually!) I got to Yale, and on top of the first file I opened, there sat a letter sent by my Master’s professor to Mr. Shaw. I love the care, professionalism, and diligence that went into this small piece of writing. In the next box, I found a file of materials my children’s choir director sent to Mr. Shaw. It had the theory workbook I used as a young singer, plus the program from a concert that I sang when I was 12. Yes! My name was in the program. I checked. Finally, I got to work. First up: Mozart One of many full scores of Mozart Requiem. Note the meticulous markings: tempos in the upper left hand corner from any recording he could find; green markings to be transcribed into orchestra parts; other colors for Mr. Shaw’s personal use. And…don’t forget to stand the chorus The first of several files of notes. Most of his notes were on yellow paper – hundreds of sheets of yellow paper. On top of this stack I found some seating and standing cues he used for one of his many performances of the Mozart. Underneath this sheet was a treasure trove of study materials: spiritual, musical, structural analysis; careful if not obsessive tracking of tempi; and multiple sets of rehearsal notes. And, with each performance, he began a new analysis, never resting on his experience alone – always finding new interpretations. Next up was Duruflé Requiem. As Mr. Shaw knew M. and Mme. Duruflé personally, his papers offered some inspiring and lesser known facts. For example, the Duruflés approved of changing all of the vocal solos to full section moments, agreeing with Mr. Shaw that this change better represented the concept of collective chant singing so associated with the Gregorian tradition. Also, in typical fanatic fashion, Mr. Shaw took note of all of Duruflé’s tempo preferences for each moment of the ENTIRE work. What a wealth of information!  “Voices are not trained to dominate, but to serve.” That was Mr. Shaw – a servant of the music and, through his music, the community. He obsessively marked every detail in green, red, or blue not to demonstrate how much he knew about the music, but rather to find the magic in the score that would help him serve it and the community better. Every yellow sheet of paper helped him overcome, not the music itself but rather the fear of not doing it justice. So, now I must go and sharpen my own pencils, find my equivalent of yellow legal pads (graph paper), and get to work on what I can do to serve the music, the performers, and the listeners. First up: Copland Old American Songs, Mahler 1, and, yep, Summon the Heroes, John Williams’ tribute to the Olympians.

3 Comments

|

Archives

June 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed